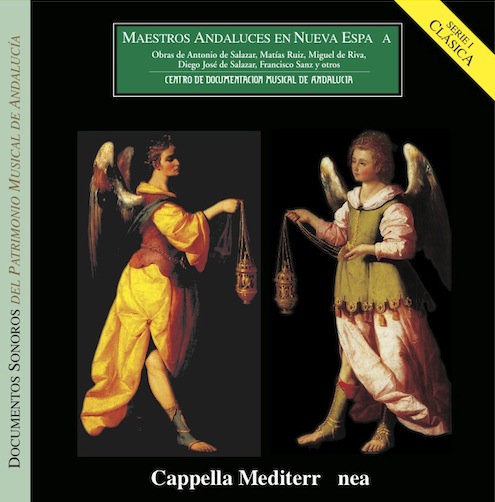

Maestros Andaluces en Nueva España

Detail DS-0139 You can buy this record here 11 € Maestros Andaluces en Nueva España Obras de Antonio de Salazar, MatÃas Ruiz, Miguel de Riva, Diego José de Salazar, Francisco Sanz y

MAESTROS ANDALUCES EN NUEVA ESPAÑA

1-Tortolilla que cantas Juan Hidalgo

2-Ay, ay que me prende el amor Diego José de Salazar

3-Al dormir el sol Sebastián Durón

4-Tarará, que yo soy Antón Antonio de Salazar

5-Cielo de nieve (instrumental) Sebastián Durón (1660-1716)

6-Zagales, oíd las ansias Mtro. Abate de Rusi

7-Ah, de la vaga campaña Francisco Sanz (ca. 1660-1732)

8-Muy poderoso señor Matías Ruiz (instrumental)

9-Ves el sol, luna y estrellas Anónimo

10-Ay cómo llora, mas cómo siente Miguel de Riva

11-Para qué los alados orfeos Anónimo (1717)

12-A la estrella que borda los valles (instrumental) Diego José de Salazar (ca.1655-1709)

13-Risueñas fuentes Antonio Rodríguez de la Vega y Torizes

14-No suspires, no llores Anónimo

15-Retire su valentía Felipe Madre de Deus (instrumental)

16-Un ciego que con trabajo canta Antonio de Salazar (ca. 1640-1715)

1- II Tiento y discurso de segundo tono Francisco Corres de Arauxo (1584-1654)

18-Afuera pompas humanas Diego José de Salazar

|

About Music and Andalusian musicians in New Spain

The musical links between New Spain and Andalusia have existed since the earliest days of the discovery and the conquest. Surely that "maese Pedro, he of the harp ", mentioned by Bernal Diaz del Castillo upon arriving on American soil with Hernán Cortés’ troops, was a member of the first group of Andalusians who came to settle in the newly-conquered America. But the passing of time, particularly after the foundation of new cities and the construction of their cathedrals, brought closer the links with the music of Andalusia. In New Spain, polyphonic works by the renowned Francisco Guerrero, chapel-master of the cathedral of Seville, and by Rodrigo de Ceballos, who held the same position at the cathedrals of Cordova and Granada, were sung during the second half of the 16th century, when both composers were at the peak of their creative talent. The circle was closed with the arrival of maestros from the Andalusian region to hold important positions in the new cathedrals of the Americas: Antonio de Salazar, chapel-master at the cathedrals of Puebla and Mexico who, according to a villancico, a popular religious song, found in Guatemala, had formerly been a prebendary in Seville, or Miguel Matheo de Dallo y Lana, who was chapel-master at the San Salvador College Church in Seville before leaving for Honduras and settling in Puebla, confirming how intimate the ties between Sevillian and colonial New Spanish music were.

One of the best collections of Andalusian music is the one that belonged to the convent of the Holy Trinity in Puebla. Founded in 1593, it paved the way in 1619 for a second convent of the Order that was to lodge the children and young ladies of the family of Alonso de Ribera Barrientos. Both convents were governed by an abbess. The period from about 1660 to 1720 saw an extraordinary musical creativity that was apparent in the masses, motets, and villancicos, sung by soloists or duets and in human tones. Today, there are more than 400 pieces that bear witness to these works by anonymous authors, different chapel-masters of the cathedral of Puebla, such as Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla, Juan García de Céspedes, Antonio de Salazar, Miguel Matheo de Dallo and Lana, Francisco de Atienza y Pineda, Miguel de Riva and Nicholas Ximénez de Cisneros; local musicians who lived in Puebla like Juan de Florentín, Jose Maria Herrera, Jose Laso Valero, Simón Martinez, Miguel Thadeo de Ochoa, Francisco Vidales, Juan de Vaeza Saavedra and Jose Mariano Placeres Santos; also of chapel-masters from other cities, including Francisco Lopez y Capillas, Fabian Perez Ximeno and Jose de Agurto y Loaysa from the cathedral of Mexico, Brother Martín de Cruzelaegui, organist of the College of San Fernando and Jose Mariano Mora of Valladolid de Michoacán. Other names we find here are those of illustrious composers from the Iberian peninsula, such as Pedro Ardanaz, chapel-master at Pamplona and Toledo; Diego de Cáseda, who held the same position at the Pilar Basilica in Zaragoza; Cristóbal Gallan, Juan Hidalgo and Carlos Patiño, masters of the Royal Chapel; Vicente García, chapel-master at Valencia cathedral; Francisco Marcos Navas, composer of zarzuela light operas, harpist and royal psalmist ; Brother Gerónimo González, active composer in Madrid and Seville; Pedro Rabassa, chapel-master at of the cathedrals of Valencia and Seville; Brother Francisco de Santiago from Portugal, who was director of music in Seville, Alonso Xuárez; chapel-master at the cathedrals of Cuenca and Seville, Mathías Ruiz, a composer from Madrid; Jose de Torres, conductor of the Royal Court Orchestra at the turn of the 17th century. Present in the collection there are also some Italians who served at the courts of Philip V and Fernando VI, such as Francesco Corradini and Giacomo Facco. And there are a few other absolutely unknown composers such as Abate de Rusi, author of one of the few secular pieces of New Spanish colonial times.

This disc includes works chosen to mark Andalusia’s presence in this New Spanish convent: Sebastián Durón (1660-1716), organist in Zaragoza, Seville (in 1680) and Palencia, and chapel-master at the Royal Court, composed the duet Al dormir el sol en la cuna del alba, a delicate Christmas carol that clearly expresses the spirit of Spanish baroque music of the 17th century; the Christmas carol to the Archangel San Miguel, for two sopranos and basso continuo, Risueñas fuentes by Antonio Rodriguez de Vega y Torices, chapel-master at the San Salvador College Church in Seville around 1690-1692; a solo amatorio called Ay Ay que me prende el amor by Diego Jose de Salazar (d. 1709), head of the Cathedral of Seville between 1685 and 1709. This song appears in the same manuscript where we find the solo Ves el sol, luna y estrellas, also a tono amatorio, by an unknown composer, although the style reminds us of Diego Jose de Salazar, possibly the author of both songs. The disc also includes Afuera Pompas Fúnebres, a four-part villancico to Our Lord by the same chapel-master. This piece is an example of the finished article a type of song that, in the early 18th century, yielded to the influence of the Neapolitan style. We also have the three-part villancico to St. Joaquin Ah de la vaga campaña by Francisco Sanz (d. 1732), a native of Montilla (Cordoba) and chapel-master at Malaga cathedral from 1684 to 1732. Aurelio Tello

|