Romanzas de Dúos y Zarzuelas

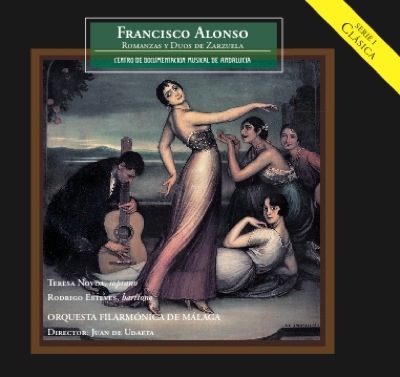

Detail DS-0146 You can buy this record here 11 € Romanzas de Dúos y Zarzuelas Francisco Alonso

1. Romanza(de “Rosa la Pantalonera”) 3'45

2. Habanera (de “Rosa la Pantalonera”) 3'17

3. Claveles Granadinos (de “24 horas Mintiendo”) 2’58

4. Canción de la Reja (de “Forja de Almas”) 2’58

5. Pasodoble (de “Forja de Almas”) 2,44

6. Romanza (de “Curro el de Lora”) 3’28

7. Dúo (de “Curro el de Lora”) 9’00

8. Raconto de Curro (de “Curro el de Lora”) 3’32

9. Bolero (de “Curro el de Lora”) 3’48

10. La Cautiva (“Canción Morisca”) 3’25

11. Cesticas de Fresa (“Pregón granadino”) 3’36

12. “La Carcelera” (“Canción Andaluza”) 2’55

13. Pasodoble (de “La Rumbosa”) 4’06

14. Dúo de Maribel y Montiel (de “La Picarona”) 4’14

15. Bolero (de “La Castañuela”) 2’33

16. Danza Gitana 5’53

17. Nana Murciana 3’59

|

About The composer Francisco Alonso, who in his time was known as ‘maestro Alonso’, belongs to the second generation of twentieth century Spanish composers of theatre music. This group of composers, better known as the ‘Generation of the Masters’, includes such eminent figures as José María Usandizaga, José Padilla, Juan Vert, Reveriano Soutullo, Federico Moreno Torroba, Jacinto Guerrero, Pablo Sorozábal, Conrado del Campo and Jesús Guridi, amongst others. They each left a large amount of theatre music, resulting in one of the most productive periods in the history of Spanish zarzuela (light opera).

Francisco Alonso López (Granada, May 9 1887 – Madrid, May 18 1948) was born into a family that belonged to the wealthy bourgeoisie of Granada at the end of the nineteenth century. His musical education began at home, where he received piano lessons from his mother, an amateur musician. Later he studied with Antonio Segura Mesa (teacher of Federico García Lorca and Ángel Barrios), and with Celestino Vila Forns, chapel master of the cathedral of Granada. Alongside this, Alonso began a medical degree, which he later abandoned for the life of a professional musician, as Barbieri and Chueca had done so before him.

Alonso’s first compositions were three short theatre pieces based on texts by Manuel Medina Olmos, rector of the school Escuelas Pías. They were entitled La primera gracia, Escuelas del Ave María and El día de inocentes, the latter of which was the first published work by Alonso. These works initiated one of the most prolific composing careers in the history of Spanish musical theatre: Alonso wrote more than a hundred and seventy works in his lifetime, comprising some of the most renowned zarzuelas of the twentieth century, such as La parranda, La bejarana, Las leandras or La calesera.

Granada was not the ideal environment to develop the kind of musical career Alonso hoped for. In contrast, Madrid seemed to suit him better. After arriving in the Spanish capital in 1911, Alonso quickly found his place in the musical life of the city. In Madrid, the zarzuela was reaching its climax: new works were regularly presented by several theatres, lead by the mythical Teatro Apolo, where hundreds of works were produced, sometimes to be staged just once. In a short time, the first big successes arrived in the 1920’s: La linda tapada, La bejarana, La parranda, and, most importantly, Las leandras.

At this time four composers stood out: Amadeo Vives, Pablo Luna, José Serrano and Francisco Alonso. These four initiated the revitalisation of the zarzuela grande with major works that have since become symbols of the genre, and nowadays are regularly performed and recorded. Vives’ works Maruxa (1914) and Bohemios (1920) brought him great success, and his Doña Francisquita (1923) revived the genre of zarzuela grande. Other composers, including Jesús Guridi, José Padilla, Federico Moreno Torroba, Jacinto Guerrero, Pablo Sorozábal, and Francisco Alonso himself, were quick to follow. Alonso’s contribution was remarkably significant with such crucial works as La linda tapada and La bejarana (1924), La calesera and Curro el de Lora (1925), La parranda (1928), La picarona (1930), Me llaman la presumida (1935) and Manuelita Rosas (1941). Selections from these are included in this recording.

Since the start of his career, Alonso experimented in many different genres: long and short zarzuelas, revistas (revues), sainetes (one-act comedies), musical comedies, and so on. Next to his zarzuelas he premiered several revues in the 1920’s, including La bejarana, La linda tapada and Curro el de Lora. In the 1930’s he alternated writing zarzuelas such as La picarona, La carmañola and Me llaman la presumida with the production of some of his best-known revues, like Las leandras, Las castigadoras and Las de Villadiego.

From the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic (April 1931) until long after the end of the Spanish civil war (1936-39), Alonso dedicated much of his time to composing revues and revue-like shows in an attempt to relieve the sadness in which Madrid was immersed. Las leandras, written in 1931, symbolises a new style, which was based on social stereotypes of the first years of the Republic. Several pieces from the work became popular throughout the country, such as ‘El Pichi’, the march ‘Los nardos’, the java ‘Ay, qué triste ser la viuda’ and the habanera ‘Dile al gomoso’. Nevertheless, Alonso never abandoned the composition of zarzuelas. During these years, he composed several of them, including Rosa la pantalonera, La zapaterita, Manuelita Rosas and his posthumous work, Cayetana la rumbosa.

The present recording compiles a few of the works that Alonso left. Claveles granadinos is the tenth number of the musical comedy Veinticuatro horas mintiendo, which premiered at the Teatro Albéniz in 1947. Claveles Granadinos is a typical Spanish song that is divided into two parts: copla (couplet) and estribillo (refrain). This was a typical form found in Spanish musical comedies during the last years of the nineteenth century. In this recording, a short fragment featuring the main theme (composed by Manuel Moreno Buendía) has been added to the song, functioning both as an introduction and as a conclusion. Claveles granadinos, written in pasodoble rhythm, displays one of the Alonso’s best qualities: his talent for melodic beauty. It is not surprising that Alonso is considered to be one of the best Spanish melodists of the twentieth century.

The following two tracks, Pasodoble and Canción de la reja were incorporated into the soundtrack of the film Forja de almas, which was directed by Eusebio Fernández Ardavín and premiered in 1943. Although the Pasodoble was originally composed for a wind band, the version presented here is an orchestral arrangement by Benito Lauret, who recently passed away. The Canción de la reja, with its structure of couplets and refrain, is written in the fashionable style of the cuplé. Most of the popular numbers of zarzuelas from the beginning of the century were written in this manner. The use of ayeos (cries), of typical Andalusian melodic ornamentation and cadences, and the inclusion of the guitar as an accompanying instrument, all contribute to the typical Andalusian flavour of this Canción.

Track 4 presents another well-known pasodoble by Alonso, in this instance from his one-act comedy Cayetana la rumbosa. The texts to this work are by Pilar Millán Astray and Luis Fernández de Sevilla, and it premiered at the Teatro Calderón in 1951. The pasodoble was arranged for wind band by Victoriano Echevarría, who at that time was the conductor of the Municipal Wind Band of Madrid. The piece went on to become an independent work that was regularly performed by Spanish wind bands.

The following four tracks belong to one of Alonso’s best (although, unfortunately, not very renowned) works: Curro el de Lora. This zarzuela, which is in two acts, contains an excellent libretto by José Tellaeche. The work gave Alonso much pride, and he desired to develop it into an opera. Yet its unsuccessful premiere in the Teatro Apolo during the season of 1925-1926 proved to be a big disappointment for Alonso, who considered it to be one of his best compositions. Curro el de Lora, with its extended instrumentation in an operatic style, clearly shows influences of Puccini, who was highly fashionable in Spain at the turn of the twentieth century. The audience at the Teatro Apolo was used to lighter comedies, and was not prepared for such a work. Rafael Marquina wrote in El Heraldo de Madrid:

Everything in Curro el de Lora responds to a wish for esthetical dignity that is always essential and necessary, especially for the zarzuela, a genre that has been stained by all kinds of nonsense, bad taste and little mannerisms... Everything in Curro el de Lora follows the noble goal of constructing a work of art departing from popular elements in which the substantial happily meets the artistic.’

Track 5 presents the seventh number of the first act of the work, ‘De nuevo al verla’, which is written for baritone. It occurs at a point in the play where the action stops, and a strong lyricism prevails in the melody and the orchestration. Track 6 is the second number from the same work, which is Curro’s romance entitled ‘Soy Curro el de Lora’. The piece is divided into two contrasting sections: the first part has a narrative role; the second and final part, where the orchestra plays an important part, is more lyrical and dramatic. The following number, an orchestral solo (number ten of Curro el de Lora), is a bolero, which is one of the most characteristically Hispanic dances of all times. To finish, the sound of the guitar introduces the duet of Curro and Lola ‘Tú eres otro y yo también’ (number 4 of the work). This duet, which is beyond doubt one of the highlights of this zarzuela, is a compilation of musical themes, including love, hate, and reencounter. Alonso employs a complex, multi-sectional structure, where the tempo, rhythm and character change several times to allow the two protagonists to express their feelings alternatively.

Track 9, a Danza Gitana (‘Gipsy dance’) that Alonso composed for the Iberia Trio, was premiered in Paris in 1909. Dedicated to Ricardo Villa, it received an award from the Fine Arts Circle of Madrid, and was published by Casa Dotesio in 1914. Danza gitana was originally composed for a trio of plucked instruments (guitar, bandurria and lute), although Alonso himself arranged it for different settings (there are versions for piano, wind band and orchestra). The gypsy-like musical ambience is easily recognizable in this work, with its beautiful and peculiar melody and rapid rhythms.

The CD continues with two songs by Alonso: La cautiva and Cestica de fresas. In a similar manner to the Canción de la reja, these two numbers display the so-called ‘andalucist’ or ‘alhambrian’ aesthetics, which originate from the end of the nineteenth century. La cautiva, based on a text by Jerónimo Cruz, was defined by Alonso as a ‘moorish song’. It was dedicated to singer Lidia Ibarrondo and to her master Alberti de Gorostiaga, and published by Unión Musical Española in 1944. Cestica de fresas is a ‘street cry from Granada’, based on a text by Francisco Losada.

Track 12, the duet ‘Que soy picarona se dice de mí’, is from La picarona, a zarzuela that premiered at the Teatro Eslava in 1930. The libretto is by Emilio González del Castillo and José Muñoz Román. The duet is a conversation between the two protagonists (Maribel, soprano, and Montiel, bariton), and it is contains several contrasting sections, including a short dance (jota). The vocal parts are of much interest, and involve moments of great virtuosity.

Tracks 13 and 14 come from Rosa la pantalonera, a musical comedy in two acts that Maruja Vallojera premiered at the Teatro Príncipe (San Sebastián) in 1939. The romance ‘Ni siquiera lo puedo pensar’ is the fifth number of the first act, and is very lyrical in character. After a short introduction, Alonso introduces a habanera rhythm that underlines the Hispanic character of this number. The following track is the eighth number of the same play: ¡Deja ya de trabajá!. It opens with a short instrumental prelude which contains Andalusian, or even Moorish, influences. A recitative and song from Granada follows, (Ay gitanita de Granada), with typical Andalusian cries, ornamentations and cadences. From the start of the song, which mentions the rivers of Granada (Darro, Albaicín and Genil), the tempo accelerates, the rhythm moves into a ternary form, and the tonality changes.

The following number is very different, and it returns to eighteenth century aesthetics. Track 15 is a bolero from La Castañuela, a zarzuela with libretto by Emilio González del Castillo and José Muñoz Román, which premiered at the Teatro Calderón (Madrid) on January 20, 1931. This work is Alonso’s tribute to the old eighteenth century style, and a prominent musical role is reserved for the castanets.

The renowned Nana murciana represents a genre that has always been an important part of Spanish culture: the lullaby. It is based on a text by Luis Fernández Ardavín, who also wrote the libretto of one of Alonso’s most famous works, La Parranda. The atmosphere of La Parranda is present from the beginning of the Nana murciana, which suggests that Alonso had it in mind while composing his lullaby.

In the Nana murciana, the protection of Our Lady of Fuensanta is requested for the child. The text also makes reference to the river Segura that flows through Murcia. Like most lullabies, it is based on hypnotic, repetitive rhythms and regular phrases, which are repeated throughout the different registers. The orchestral accompaniment is very effective and contributes to the necessary atmosphere of quietness and intimacy. Nana murciana is divided in two sections. The first section is the lullaby itself, and the second, more extrovert section, is a song about Murcia and its patroness, Our Lady of Fuensanta. It is followed by a repetition of the lullaby.

EMILIO CASARES RODICIO

Traducción: María Martínez Ayerza / Amy Power

|